In Mid-June, US Government employees from the U.S. Department of Commerce had their emails accessed by hackers operating on behalf of the Chinese government. This was in lead-ups to talks with China, with the targeted implication being that China simply wanted to gain some insights into the pending discussions. Microsoft gave them the designation Storm-0558.

Notably, the activity may have gone completely undetected, were it not for the fact that officials from the U.S. Department of State were also targeted. The State Department not only detected the activity, but was able to alert Microsoft to the intrusion, eventually unraveling other intrusions across 25 total organizations. For those of you doing the math, that is a 4% successful detection rate.

A point of intrigue in this case is how the Department of State was able to detect this activity before anyone else. Although it is acknowledged that the State Department was using “enhanced logging” via M365, what has not been well connected in this case is the fact that the enhanced logging was a result of the fact that this was not their first rodeo. More specifically, the abuse of “authorized” cloud application roles with permission to access emails and other cloud objects within their cloud environment harkened all the way back to 2020.

History repeats itself

In 2020 the SolarWinds attack was a well-publicized attack that took place on two fronts. On the first front is the well-known compromise of the SolarWinds Orion product itself, leading to a supply chain compromise of its customers. Less well known is the fact that M365 customers who did not have SolarWinds were also swept up in the campaign. Microsoft resellers, who had been compromised, had maintained privileged access to their customers’ M365 cloud environments. By subsequently abusing privileged access to their customer accounts, attackers could extend into customer M365 accounts completely undetected. To obfuscate this activity, they abused application access instead of user access. Both CrowdStrike, which was a failed target, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency responded. CISA released a forensic tool specifically to detect this form of intrusion.

Despite the publicity around SolarWinds, the fact adversaries were running rampant through Microsoft’s cloud and went relatively unnoticed was not well understood by a public conditioned to believe that the activity centered around SolarWinds. This goes back to our CEO Steve Jones perspective on the cloud’s unanticipated vulnerabilities in that breach. The reality, however, is stark: Application access policies were being abused to obtain sensitive information such as emails. Organizations that had built up a traditional approach to privileged access as an extension of user identities were unprepared for the fact that those privileges extended into the abstraction of application level access, and had to be monitored completely separately with a completely separate set of rules.

Microsoft downplays the impact

The most recent Chinese hacking campaign involves a vulnerability that was discovered allowing them to forge authentication tokens, and from there they were discovered abusing application access policies to retrieve customer data. If you had read Microsoft’s statement you might be forgiven for thinking that the problem was quickly identified, mitigated, and posed no future risk to customers. The advisory given by CISA tells a slightly different story.

Still, the downplay from Microsoft is in parallel to the previous statements made by them following the SolarWinds breach which called for a “global response” to cybersecurity. They cited the example of the SolarWinds malware–while completely omitting the fact that their cloud configuration was one of the primary launch points for abuse in accessing customer data. It is clear that when it comes to your cloud’s security, Microsoft believes that it is literally anyone else’s responsibility except theirs.

What can you do

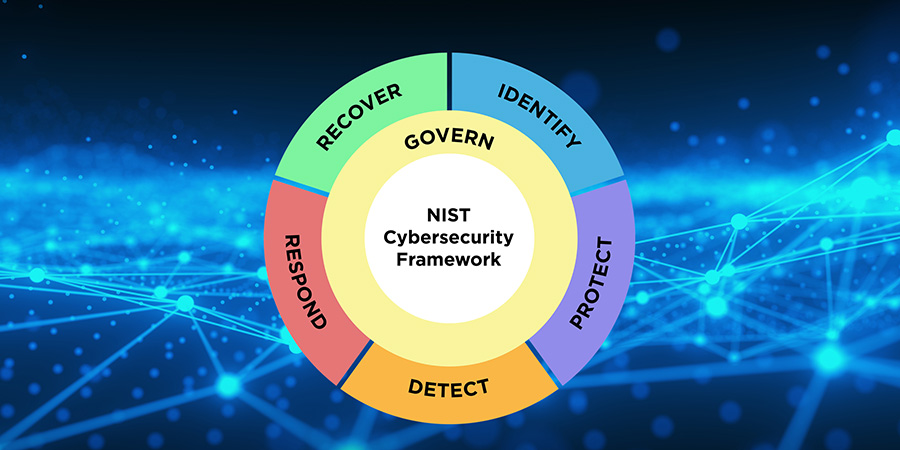

Based on the evidence available, the reality is that you are on your own. Should a similar compromise using similar vectors occur in the future, the onus will be on their customers to identify the activity — and they will have to pay for the privilege to do it, through the enablement of Premium Auditing. This by itself will not be enough to detect a compromise – you will also need to configure the rules to identify and alert on anomalous activity within your environment. To do that, you will need to follow the advice given by CISA when they say, “Understand your organization’s cloud baseline”, i.e., you need to build the rules for detection for what is and is not anomalous. We’ve seen our clients go through experiences like this, as we helped them disentangle and secure their complex environments.

What is your take on this? My two cents: As much as Microsoft states there needs to be a global response, shouldn’t there be vendor responsibility? How can the Shared Responsibility Model even work when vendors obfuscate their own security controls and leave customers to figure them out and pay extra for them?